Flocks of birds move in complex ways that are amazing to witness. Behind all of this complexity are the individual birds, moving in relatively simple ways. The intricate behavior of the entire flock really comes down to the behavior of the individuals that make it up, and this is what inspired Craig Reynolds to come up with the idea of boids (bird-oid objects) for flock simulation. He defined three simple "steering" behaviors that each individual in a flock (the "boids") has to follow:

- Separation: avoid collisions with other boids.

- Alignment: try to match the velocity of nearby boids.

- Cohesion: move toward the center of the flock.

There are other behaviors apart from those that can make the simulation more accurate to an actual flock, but I wanted to see how much mileage you can get from implementing just the three simple steering behaviors.

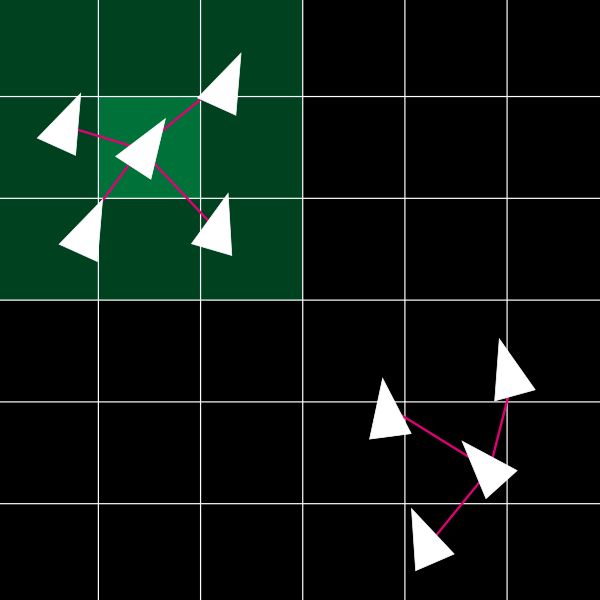

I think its interesting to see how boids behave by following only one steering behavior. It should give you a better idea of what's happening in the full simulation, since the final result is just the three behaviors summed up.

And then finally all together:

Depending on how much weight you give each behavior over the boid's movement, you can get significantly different results. I found that to get a clean result, separation is more important than alignment, which is more important than cohesion.

Performance and Optimization

In order for boids to follow the steering behaviors, they need to know their neighborhood: the other boids that are nearby and in vision. This is very inefficient since we need to calculate the distance between a boid to all other boids. Even if the boids are far enough apart to safely ignore each other, we still need to calculate the distance between them.

By computing neighborhoods in this way, I was able to get about ~400 boids running at 20 frames per second. I was happy with this result, but I knew it could be improved. I've seen other implementations handling thousands of boids at even higher frame rates. So how are they doing it?

The most common method of boid optimization (that I could find) is to separate space into a grid, and then find where each boid falls on this grid. This allows you to compute neighborhoods by only considering boids that are in nearby grid cells. This can drastically reduce the number of boids that need to be considered for each neighborhood.

If you have a flock of 1000 boids and you're doing no optimizations, you need to consider 999 other boids as the potential neighborhood of a boid. With the grid approach, each boid might only need to consider a couple dozen other boids as potential neighbors, rather than hundreds.

After implementing grid optimization and tuning the settings (grid tile size and boid view distance), the frame rate at 400 concurrent boids increased from 20 FPS to around 160 FPS. At 1000 boids, the simulation runs at around 100 FPS with the same settings, but it largely depends on how close the boids are to each other. If they are densely packed together, grid optimization does not work very well.

I found other downsides of the grid optimization is that it can reduce the quality of the simulation. If you decrease the tile size you gain performance, but the boids can start acting too independently from one another. With very small cell sizes for the grid, boids ignore pretty much every other boid apart from the ones very close to itself. So, sure, you can run thousands of boids at once, but they're not really behaving like boids. You need to find a balance between tile size, performance, and "flock-like" behavior.

Additional Improvements

Apart from the three simple steering behaviors, what else is there to implement? How can the simulation be improved?

I have no clue. But Craig Reynolds does. He goes in-depth into his original boid implementation in his 1987 paper. From there, I can tell that the most significant addition to be made is obstacle avoidance: have boids avoid obstacles by steering away from them. At first I didn't think this was complicated, but the key component for this feature is boids have to steer around obstacles. So if a boid is following a path that is blocked by an obstacle, it should adjust its path to overcome it and not just simply fly away from it.

Beyond that, other significant improvements that can be made are:

- Simulate in 3D instead of 2D.

- Have boid movement be acceleration based. This would result in a more fluid simulation.

- Have boids prioritize the different steering behaviors dynamically. If collision is imminent, a boid should prioritize the separation behavior over alignment and cohesion.

- Better optimization method. The grid method works well enough, but there are other methods that work better. I recommend reading this article that details how to use DBSCAN (a machine learning algorithm) to optimize boids.

- Make boids steer toward goals.

I highly recommend Reynold's post about boids on his website. He has an interesting list of different ways swarm behavior has been applied, from movies to sorting algorithms. It's a great resource to learn more.